GC Committed to a New 3-Year Global Park Defense Program to Support Komodo Island and Dragons

Update: 06/20/25

A komodo dragon uses its long, forked tongue to locate prey by analyzing scent particles and determining the direction of the source. All photos by ©Paul Hilton.

Nestled in the heart of Indonesia’s archipelago lie the volcanic islands of Komodo National Park (KNP). Rolling green hills, dry savannahs, and white and pink sand beaches make up the park’s three large islands (Komodo, Padar, and Rinca) and a legion of other smaller islands, surrounded by clear blue water.

Under the ocean’s surface, manta rays, whale sharks, and over a thousand species of tropical fish thrive among an abundance of other species of animals and corals. On land, deer and buffalo roam beside the park’s most famous animal: the Komodo dragon. Recently, Global Conservation committed to a new 3-year Global Park Defense program, supporting the Komodo Survival Program, which includes:

Renovation of West Komodo Ranger Station and dormitories for police and law enforcement rotations

Purchase of a Rapid Sea Patrol Vessel to be stationed full-time on the West Coast of Komodo Island

Marine radar deployment on the West coast of Komodo Island to detect illegal vessels, especially at night, for rapid interdiction.

Introduction: A Park for Dragons

Nestled in the heart of Indonesia’s archipelago lie the volcanic islands of Komodo National Park (KNP). Rolling green hills, dry savannahs, and white and pink sand beaches make up the park’s three large islands (Komodo, Padar, and Rinca) and a legion of other smaller islands, surrounded by clear blue water. Under the ocean’s surface, manta rays, whale sharks, and over a thousand species of tropical fish thrive among an abundance of other species of animals and corals. On land, deer and buffalo roam beside the park’s most famous animal: the Komodo dragon.

It is unsurprising that these lizards are called "dragons." Often weighing more than 300 pounds, these giant lizards can grow up to 10 feet long, run as fast as 12 miles (19 km) per hour, smell blood from almost six miles away, and deliver a powerful bite with venom in their saliva strong enough to kill a human. As the largest, most aggressive animal in the park, they are at the top of the food chain.

While they eat a wide variety of animals, ranging from rats to adult buffalo, their numbers have declined. There are now fewer than 3,500 dragons left in the park due to human-caused habitat loss, illegal hunting, and climate change. Consequently, they are classified as Endangered on the IUCN’s Red List.

KNP was initially established to protect the Komodo dragon and its remaining habitat in 1980. In 1991, due to the park’s dedication to protecting its land and marine life, it was officially designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Despite efforts to protect the park and all life that relies on it, KNP has been and still is under threat of further human impact.

Marine patrolling in the waters surrounding the islands is crucial to keep underwater habitats healthy and flourishing. Illegal fishing, including blast fishing, which uses explosives to kill fish, is indiscriminate. Massive sections of reef become underwater wastelands, thereby providing no habitat for fish to stay and no sustainable fishing in the future.

Given the sheer size of the park, one of the main issues preventing effective protection is a lack of monitoring and reporting. Without access to the technology necessary to thoroughly survey the land, there is no way to ensure that conservation guidelines are being upheld and that there are no illegal actions taking place in the park. It also means that, even when human-caused impacts are discovered, there is often a lack of accountability for actions that intentionally or unintentionally impact the environment in illegal or negative ways.

The large size and mountainous terrain of Komodo NP make patrolling a challenge for the dedicated rangers. Global Conservation provides SMART technology, radar, drones, and stationary cameras to ensure the capture or expulsion of poachers.

The beauty and impressive biodiversity above and beneath its oceans' surface make the park an ideal destination for the tourism industry, which thrives there. While prosperous for the local community's economy, tourism can be detrimental to the environment. Visitors bring in the funds that over 3,200 people living in the park and over 16,800 others living in the surrounding areas need to survive. However, because the only way to travel within the park is by foot or by boat, the more people exploring the islands, the more pollution from boats and the more foreign substances from visitors' shoes.

Improving Protection and Monitoring in Komodo National Park

Recently, the Komodo Survival Program has developed a plan for building a larger, integrated ranger station and dormitory in Loh Wenci, a remote location on the west coast of Komodo Island. This preparation involved intensive meetings with the National Parks authority and the Department of Housing and Infrastructure of Manggarai Barat to ensure compliance with regulations and administrative procedures. The KSP collaborated with a Balinese architect to finalize the building design and detailed engineering design (DED). Following the completion of the DED, we conducted a site visit to clear the land and identify the construction location. The director of Komodo National Park graciously joined the team, staying overnight at the site to discuss and oversee the construction plans and preparatory activities.

Currently, the construction site has been cleared and fenced for safety, and some construction materials have already been shipped from Labuan Bajo to the site. The construction of the ranger station (main office building) is set to begin in September and is anticipated to be finished by January or February 2025 at the latest. The second stage of construction, which includes the ranger dormitory, is scheduled to commence in May 2025.

A baby Komodo dragon is confiscated…

And four poachers are arrested.

In October 2023, the Labuan Bajo Quarantine Agency thwarted an attempt to smuggle a juvenile Komodo dragon at the ASDP Labuan Bajo ferry port, believed to have come from the Komodo National Park. A joint team, comprising members from the Komodo National Park Agency, the East Nusa Tenggara Natural Resources Conservation Agency, GAKKUM, and the Komodo Survival Program, identified the Komodo dragon and coordinated with the Manggarai Barat Police Department. Shortly thereafter, the Manggarai Barat Police apprehended four individuals involved in the smuggling operation. During a 2024 court hearing, the Komodo Survival Program provided expert testimony. The four suspects receiving prison sentences ranging from 2 to 4 years.

Patrol operations

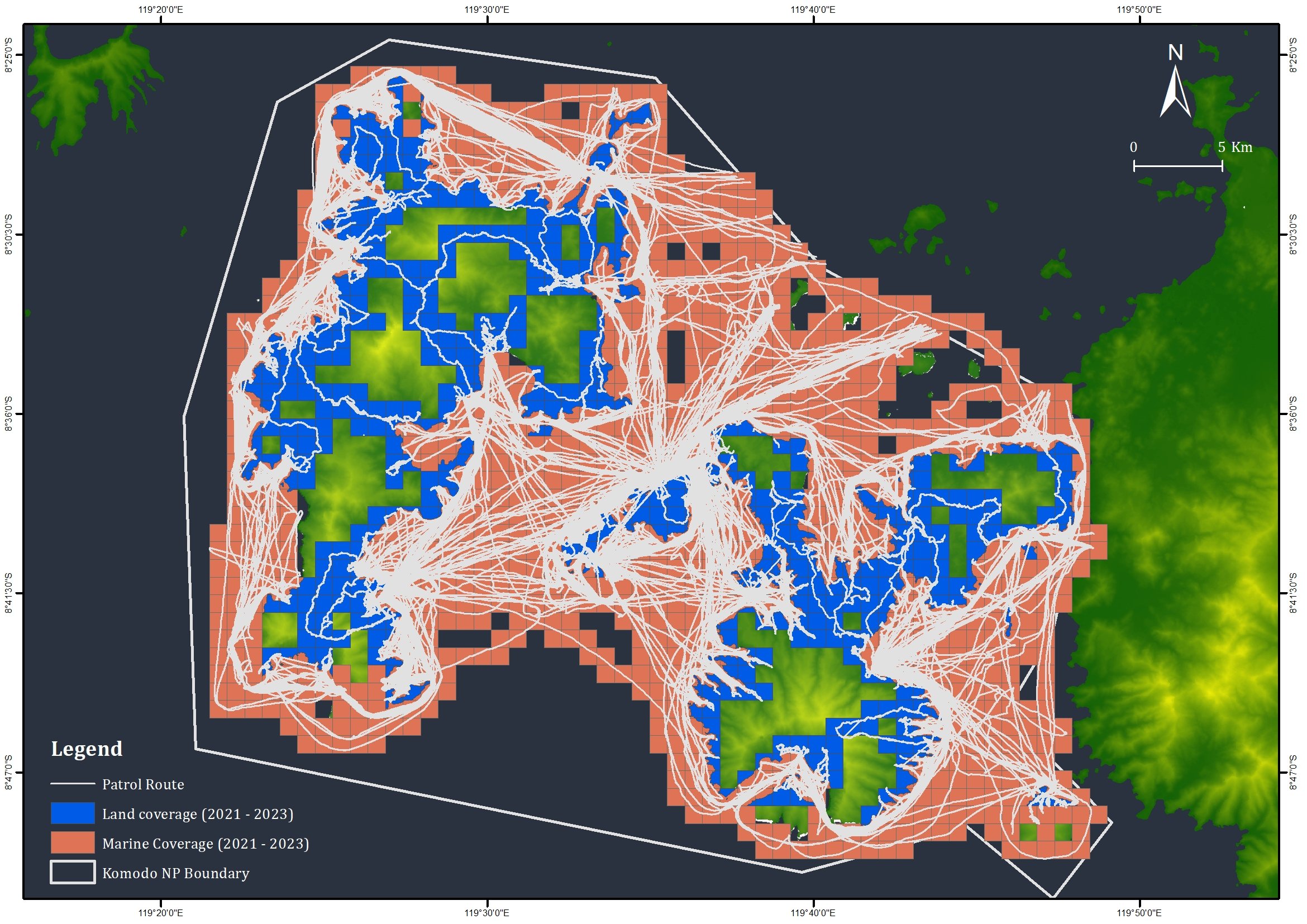

Despite a major allocation of funds to the construction, we have still managed to conduct regular patrols. This year we covered a We covered a total of 22,370 km across land and marine, covering an area of 75,000 ha. The patrols have mainly targeted violations related to non-tax revenue of KNP permits, illegal fishing, and poaching activities.

KNP headquarters summoned a total of 30 tour operators and issued written warnings for their violations. Based on how often violations were seen and how much money was lost, we think that tour operators and visitors skipping KNP non-tax revenues (entry fees and other park-related fees) costing the park up to one million dollars per year.

On September 8th, police arrested tree poachers from Bima at Sape, Sumbawa Island, West Nusa Tenggara, using ten deer as evidence.

To combat poaching, this year we installed six online and 21 offline surveillance cameras. We successfully recorded two instances of poachers entering the park in June and July. This finding was followed up by the Park Director who strengthened coordination with GAKKUM, East Nusa Tenggara Police, and West Nusa Tenggara Police. Successful outcomes have resulted from these partnerships.

A busy virtual map shows how many patrols are being completed around all of Komodo National Park, with special consideration for entry and exit points that poachers use.

FUTURE RECOMMENDATIONS:

Continue to increase the patrol support due to the high risk of marine violations in the prioritized area around the 4 ranger stations (Loh Wenci, Loh Wau, Loh Padar Selatan, and Loh Baru).

Involve other stakeholders, especially GAKKUM (Ministry of Environment and Forestry Law Enforcement Bureau), to increase the frequency and quality of integrated terrestrial patrols.

More regular coordination meetings among stakeholders, KNP, GAKKUM, and others.

Support investigations and law enforcement collaboration between KNP and GAKKUM.

Global Conservation Commits to a New 3-Year Global Park Defense Program

Global Conservation’s Executive Director, Jeff Morgan, went on a mission to Komodo National Park in September 2023, meeting with the National Park Authority and GC Partner in Conservation, Komodo Survival Program.

Global Conservation has been funding over $200,000 for park and wildlife protection to deploy Global Park Defense against wildlife poaching and illegal fishing over the past two years. Overall improvements in park and wildlife protection include:

Supporting a 50% increase in both land and marine patrolling.

Confiscation of boats, bombs, illegal fish catch, and compressors.

There has been an increase in patrolling in terms of distance and frequency, especially in areas previously unpatrolled, finding new signs of illegal bomb fishing and deer poaching.

Training all Komodo Park Rangers in SMART Patrolling Protection and Biodiversity Data Collection

Integration of SMART with the National IMS Dashboard is now a model for all national parks in Indonesia.

In 2024, Global Conservation has committed to a new 3-year Global Park Defense program, supporting the Komodo Survival Program, which includes:

Renovation of West Komodo Ranger Station and dormitories for police and law enforcement rotations

Purchase of a Rapid Sea Patrol Vessel to be stationed full time on the West Coast of Komodo Island

Marine radar deployment on the West coast of Komodo Island to detect illegal vessels, especially at night, for rapid interdiction

With the new GC-sponsored Marine Radar, illegal entry into the National Park at night will be far more difficult.

On Komodo Island's West Coast, deer poachers hunt at night, sometimes taking up to 20-30 animals, which can fetch up to $500 each in local Sumbaya meat markets. For example, there was an instance in 2019 where a boat with over 90 deer poached in Komodo National Park was intercepted by authorities.

Rangers find illegally harvested animals, including this near-threatened white tip reef shark.

This new commitment also includes increased Marine Protection against illegal bomb fishing and enforcement, for the first time, of No-Take Replenishment Zones within the National Park.

With renewed commitment by the Indonesian government to maintain staffing levels of full-time rangers and consultants, Global Conservation’s critical investments to stop illegal poaching and fishing will continue to secure the future for Komodo National Park and stable dragon populations for years to come.