Tech for Parks:

Drones

Over the last decade, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), also called drones, have become one of the most important pieces of technology in conservationists’ toolkits. They have a wide range of applications, from wildlife monitoring to tracking poachers.

Consumer drones first hit the market around 10 years ago, but the industry only took off with the launch of DJI’s Phantom 4 and Mavic Pro in 2016. Consumer drones have quickly dropped in price and risen in quality since then.

Drones are often considered to be an excellent alternative to light aircraft, which have been a historically important tool in conservation. However, light aircraft have serious limitations: they’re very expensive and they’re dangerous. In fact, light aircraft are the number 1 killer of wildlife biologists on the job, killing 60 biologists and other scientists in the field between 1937 and 2000. In that same time, 31 scientists died on the job from all other causes combined.

Aside from this, drones have several advantages over human pilots or biologists on foot: they can be operational nearly at all times, are unhindered by heavy forest cover, and of course, do not need to eat or sleep.

The two main types of drones on the market are fixed-wing, which look like airplanes, and rotary-wing, which have rotating blades like helicopters. Fixed-wing drones are used in situations that require speed or long distances, as they can fly farther and faster on a single battery than a rotary-wing drone. Rotary-wing drones, on the other hand, are able to fly at very slow speeds, and can even hover in place, an impossibility for a fixed-wing drone. Both types can carry cameras or sensors to collect data or images, or even stream live video back to the user.

Drones can be equipped with a wide range of cameras and sensors, such as high-resolution still photo cameras, video cameras, multispectral sensors, thermal cameras, LiDAR or other laser scanners, and instruments to measure temperature, humidity, or air pollution. Larger drones can lift sampling equipment, cargo, or emergency supplies.

Among many other incredible applications, scientists are using drones to count orangutan nests in the Leuser Ecosystem of Sumatra. Here are a few other ways that drones are being used by conservationists today:

U.S. National Park Service rangers in the Grand Canyon, USA, are using drones to search for missing hikers.

Scientists used drones to count a newly discovered supercolony of 1.5 million Adelie penguins, after it was found using satellite imagery.

African Parks rangers in Malawi are testing the use of thermal cameras to detect and deter poachers entering Liwonde National Park at night.

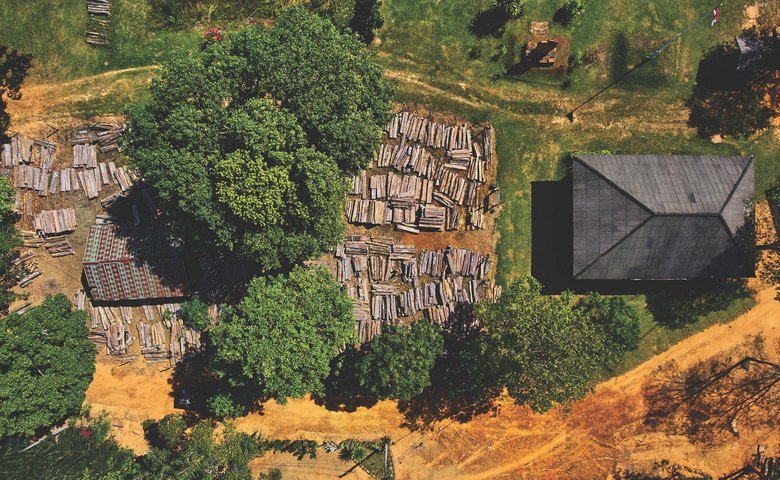

The Amazon Basin Conservation Association is using fixed-wing drones in Peru to quickly investigate reports of deforestation in a vast, dense rainforest reserve with no paved roads.

Australian rangers are using drones at sea turtle nesting sites to monitor beaches for the tracks of feral pigs, which are nest predators. When they’re found, rangers deploy to cull the invasive pigs. They can also use the aerial view of the turtles’ tracks in the sand to determine which species of turtle are nesting on a given beach, and how many nests there are.

Scientists at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK are using thermal images captured by drones to identify and count wildlife on a landscape scale. At night or in dense vegetation, thermal cameras show animals as brightly glowing spots against a dark background, like stars in the night sky, so these scientists are using methods from astronomy to automatically count and classify the wildlife.

They are also commonly used for wildlife counts, habitat mapping, behavioral observations of large species like whales, monitor alien plant invasions, check on the condition of infrastructure like fences, and map burn scars or erosion.

As technology continues to improve and drone price continues to drop, conservationists will undoubtedly find an increasing number of uses for this versatile technology.